As the topic of race and racism in America rises to the forefront of both social and editorial media, the nation of South Africa is once again alluded to by pundits and posters alike. South Africa is a country whose name is synonymous with racism and the former system of Apartheid that lasted from 1948 to 1994. However, an allusion loses its weight without a firm grasp of South Africa and its history (particularly Apartheid).

Officially known as the Republic of South Africa (RSA), and as the name suggests, it is located in the southernmost region of Africa. It shares a border with Mozambique, Eswatini (formerly Swaziland), Lesotho, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Namibia. It is in no way homogeneous, and there are over 10 different languages. The largest four languages are Zulu (22.7%), Xhosa (16%), Afrikaans (13.5%), and English (9.6%), and, according to the 2011 census, 76.4% is African, 9.1% is white, 8.9% is coloured, 2.5% are Asian, and the rest are uncategorized at .5%.

When it comes to the talk of “peoples” in regards to South Africa, one needs to take extra caution due to the politicization of anthropology under Apartheid. The lexicon surrounding who is called what is one that changes with the multiple changes in regimes with different ideological perspectives. Similar to usage of words like Native American, or (p)erson (o)f (c)olor, language is a primary tool used by settler-colonial states to enforce, what are ultimately baseless, categorizations of people into “races”.

Racial notions like “white” and “black” as distinct psuedo-ethnic categories that, while utterly arbitrary and baseless by themselves, are given weight when combined with their settler-colonial state’s respective cultural and economic hierarchy. Race is merely the result of an intrusive state—populated in part through the importation of diverse settlers—to fabricate a method to ideologically rationalize the demographic and hierarchical chaos it is born into. It is no coincidence that notions of racial identity take primacy in the settler-states of Brazil, Israel, the US, Australia, and so on. On the other side, you have the prejudice/disparity in Berlin as between Turk and German (not white vs. poc). South Africa, despite being in the so-called “Old World”, must be understood in a racialized context.

The demographic landscape of southern Africa is commonly described using the term “Khoisan”. Khoisan is catch-all to refer to the non-bantu language-derived-speaking people in this part of the world. To say that southern Africa has been inhabited for many years would be an understatement. The first group of anatomically modern Humans (Homo Sapiens Sapiens) that broke away from our predecessor ventured south and would eventually come to be the Khoisan.

The word Khoisan is etymologically a combination of the Khoi and the San people who share a good deal of certain cultural characteristics. They were arguably “there first”, and they were present in southern Africa for a long time.

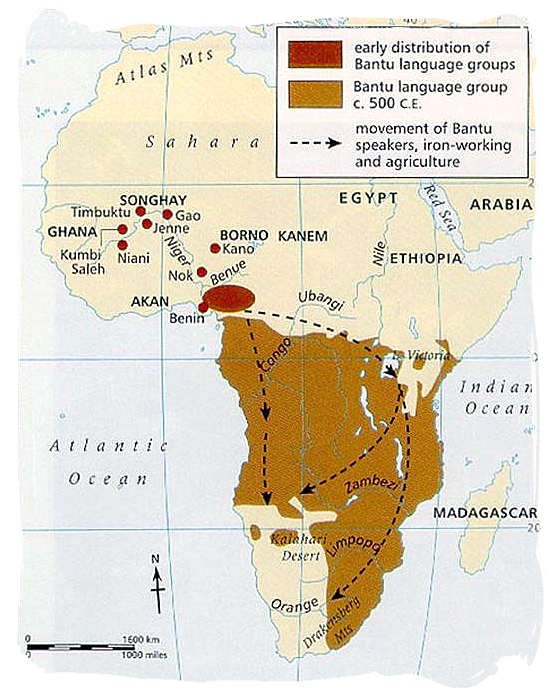

Fast forward to the 2nd Millennium, and originating somewhere in West Africa/present-day Cameroon, there were people, who are theorized to speak some sort of “proto-bantu” progenitoral dialect. In much the same way that linguists constructed “proto-indo-european”, they have constructed “proto-bantu”. It is part of the broader Niger-Congo language family.

The Bantu Migration

These people/peoples began a period of mass migration that would forever change the demographic landscape in a period known as the Bantu Migration (akin to the Germanic Migration in Europe). It was not a continuous long march, but rather a period in which peoples organically dispersed in waves (or to split off). The whole process did not end until sometime before the turn of the 16th century.

Most of the present-day peoples in central, southern, and south-eastern Africa speak a language that can be traced back to more or less a single language (proto-bantu). For South Africa, these people, having the advantage of metalworking, would eventually push/absorb the Khoisan by c. 400 – 500 CE. These people include the coastal descendants of Nguni (Zulu, Xhosa, Swazi, and Ndebele), the Highveld descendants of Sotho-Tswana (Tswana, Pedi, and Basotho), and the north-eastern descendants of Venda/Lemba/Tsonga.

It is at this point in the narrative that the term “Bantu” falls to the way-side, as, today, the term has a strong connotation to the Apartheid regime. The National Party (the propagators of Apartheid) racialized the term to describe all Africans. It was previously considered the preferred term, over native, before the rise of the Afrikaner nationalists.

The Afrikaner story is the story of colonization.

The Europeans come upon the Cape of Good Hope (actually a misnomer like Greenland), and the Portuguese sailor, Bartolomeu Dias, rounds the Cape in 1488 CE. The region was naturally very coveted for its obvious commercial potential for Indian trade. The Portuguese are frequently the first imperialist to the scene, and they made landfall a few years later in 1497 CE.

It wasn’t until 1652 CE that a permanent colony was established at the Cape. The Dutch East India Company (VOC), under Jan van Riebeeck, and the ethnic descendants of the African Dutch settlers would become known as the Afrikaners (speaking Afrikaans).

The English come into the scene in 1795 when they seize the Dutch Cape colony. Even after England monopolized regional European colonization, it was not until the turn of the 20th century that the UK finished conquering the interior. It is during this period that England is driven by the sole desire to unify all of southern Africa under a single settler-state, and there was heavy resistance.

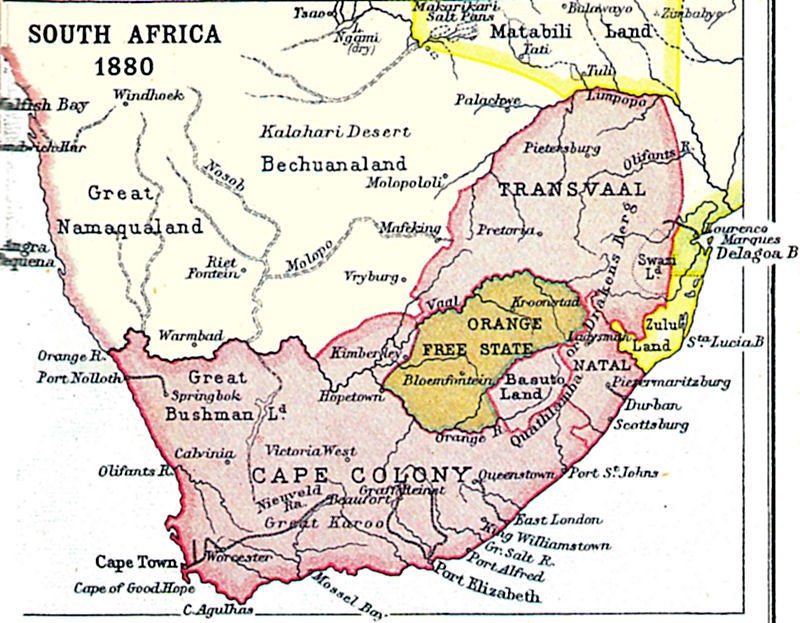

As the British expanded their influence and control over more coastal territory—creeping closer inland—the tensions between the newly arrived English and the already-present Dutch in the Cape Colony (the Boers) results in the Great Trek (1835 – 1840). The De Grote Trek saw a mass migration of the Boers into the interior and the eventual establishment of two independent Boer republics. There is the Orange Free State (or OVS) which exists in a province today known as “Free State”. Further inland, in the Transvaal, north of the Vaal river, there was the Transvaal Republic. The OVS was founded in 1852, and the Transvaal Republic (later the South African Republic after the 1st Boer War) was founded shortly after in 1854.

South Africa – 1880

The Boers desired more isolation in the rural areas and tried to keep away from British law and language. In this regard, they are very similar to the Pennsylvania Dutch in the United States. A major difference in their cultural trajectories, besides the passive Pennsilfaanisch-Deitsch establishing good relations with pre-eurocolonial peoples, is that the British administration was overly aggressive towards the Afrikaners. The belligerence of the British can be explained by the Afrikaner’s desire for an independent nation-state.

The attempts by the UK to annex the two Boer states during the 1st Anglo-Boer War (1880 – 1881) failed, and it wasn’t until the 2nd Anglo-Boer War (1899 – 1902), that England finally annexed them. The British failed to instill notions of race, and this process did not make head-way until unification into the Union of South Africa in 1910. Four years later, in 1914, the Nationale Partei (National Party or NP) was founded by these same Boers, and their rage over the annexation fuels the NP’s future racial autocratic regime.

During this same period, the growth of African political entities, most notably the imperial Zulu Primacy (1816 – 1826) of Shaka Zulu, shows the continued existence of traditional modes of power. This primarily meant that in rural African villages, young men, desiring the money to buy cattle (and with it wife and land) in their home, would venture into mostly Afrikaner South Africa to work as migrant laborers in the mines (and the like). They lived and worked at these enterprises, never really venturing out or sticking around, and the South African capitalists grew heavily enamored/dependent with/on this system of migrant labor.

Colonial Period of South Africa

As the South African colonial administration grows in power and reach, the economic landscape of South Africa grows more capitalistic. The creep of colony and capital was in perfect unison, and as more capitalists needed more migrant laborers, more land was incorporated in the colony. This creates a contradiction that forms the material basis for Apartheid.

Over time the reach of capital and colony began to erode the traditional ways of life in the same rural areas that supplied migrant labor. At some point, when the communal ownership of land was supplanted by private land ownership, the youth no longer were able to get the land in their home village. Without the ability to obtain a way of life in the rural areas, these youths ventured into South African towns looking for work. It is a tale seen throughout the world at this time.

Private Afrikaner capital grew restless as the influx of previously rural Africans into the urban areas threatened their ability to profit off of mines, and the Afrikaner lower classes grew restless over the threat of Africans taking Afrikaner jobs. Private capital wanted the migrant laborers AND it intrinsically needed the growth of capitalism into these migrant’s homes.

It is out of the desire to essentially overcome the migrant labor contradiction through brute state- power that the idea of Apartheid was born.

In 1948, the [Reunited] National Party won, under Daniel François Malan, the elections and finds itself in sole control of the government. The party had two objectives: Assert Afrikaner cultural dominance and force the African population to live ONLY in the rural areas to maintain the migrant labor system.

Apartheid is an Afrikaans word meaning “seperate-ness”, and it was not a specific set policy laid out in 1948, but was rather an organic process of escalation by succeeding Afrikaner governments. Competing ideas of how to handle the contradiction swayed from total social and economic separation to the “moderate” pragmatic view that was ultimately favored.

As the contradiction between migrant labor and the expansion of colonial capital could not be simply brushed under the rug, the dialectical conflict’s growth was matched by an increase of South African government domestic and foreign policy belligerence.

The general concept of NP domestic policy was a paired attempt to contain Africans to designated rural zones (i.e. reservations) while working to develop distinct institutions within these same reservations (later known as the Homelands). The NP reasoned that the erosion of pre-eurocolonial institutions was the main source for the increasing African urbanization. To address this they decided to “re-create” a facsimile of African pre-eurocolonial institutions, in designated areas, and, ideally, have their cake and eat it too. It was doomed to fail from the beginning as the introduction of a new mode of production would ceaselessly push the society towards urbanization.

This was first alluded to in 1923 with the Native Urban Areas Act, which gave municipalities greater powers to segregate housing, police African communities, and restrict movement. The percentage of Africans living in urban areas rose from c. 10% to 23% between the years 1904 and 1946.

It is worth noting that the rise of urbanization among African people coincided with the annexation of the Boer republics and the subsequent hegemony finally achieved.

Just as the colonization of Southern Africa was piecemeal, the response to it paired as well. The NP found collaborationist “chiefs” who acted on the behalf of Pretoria in a gambit to regain, or simply seize, power, and influence in the rural areas.

The NP ruled South Africa as essentially a one-party state until a compromise was reached with Nelson Mandela and ruling Frederik Willem de Klerk. The compromise resulted in the first free elections, under a new constitution, and Mandela won in a landslide victory of the African National Congress.

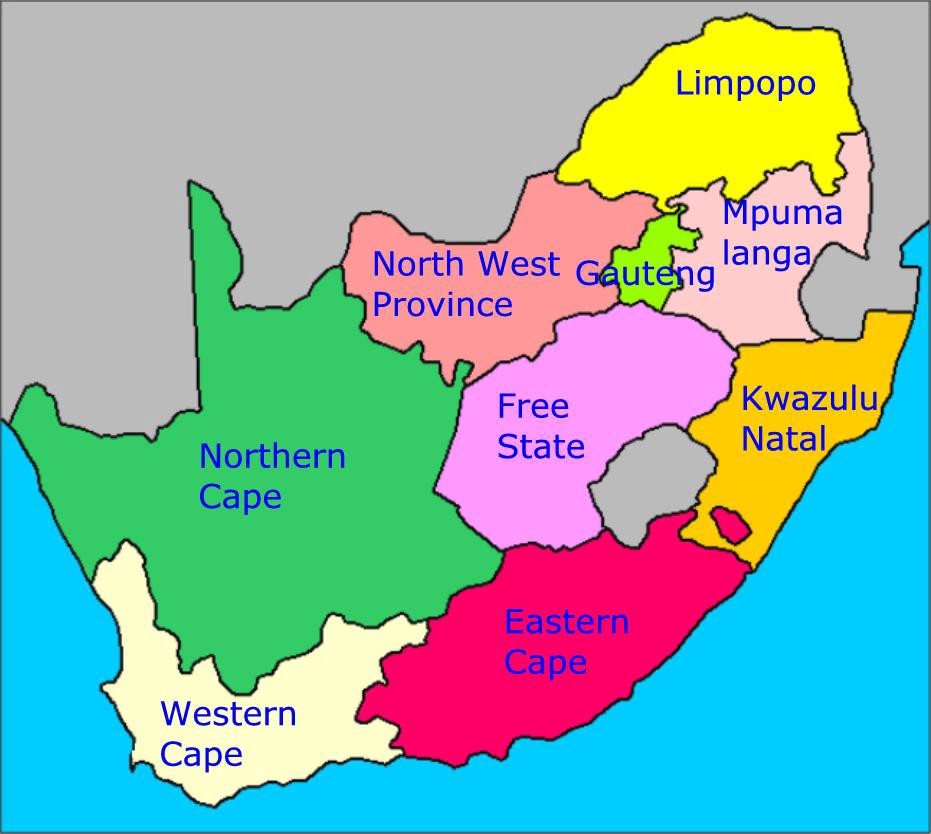

Provinces of Contemporary South Africa

Looking at contemporary South Africa (or ZA), the brutal irony is that wealth inequality and xenophobia has increased since 1994. South Africa is in a very uncomfortable socio-economic and political situation. Apartheid has only ended just under 30 years ago, and the time it takes to undo structural inequalities is a grim reality that many people in the United States can resonate with.

The reason South Africa needs to be understood is that it is dealing with, in many ways, the same institutional racial inequities as the United States (among others). There is an argument to be made about how seeing yourself in another’s struggles can give unique learning-experiences. For the United States, the “separate-ness” only de jure ended–not reservations however-–with the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

The truth is that ending Apartheid was not enough, and the South African government has had slow success in actually destroying Apartheid. This lack of success has resulted in the current ZA political climate, since 1994, has become more xenophobic, and having only increased wealth inequality (using consumption expenditure data). Not to mention the rising tide of violence against women which sees a woman killed every 3 hours.

(A)frican (N)atonal (C)ongress flag waved at a rally

One specific example of this phenomenon can be seen in the areas surrounding the former Homelands. Under the NP, Africans could not buy the very fertile lands outside the Homelands, and despite the ANC having removed this restriction, few people can actually afford it. A government program that was started to help purchase and redistribute this type of land fell apart shortly after it started. The result is that poverty and racial inequalities remain. It is not like the white population is moving into the countryside. The bulk of virtually all economic and infrastructure development done since the start of the 20th century was focused solely on the urban, white populated, areas.

Looking at maps of elections, race, income, and so on, it is painfully obvious where the small section of economic opportunity exists. The ANC had increased the competition for the few good jobs, and without the resources, it could not create more jobs to meet this demand. For 2017, the black South African unemployment rate was 31.4%, and the white South African unemployment rate was only 6.6%. The average white income is six times that of the average black income. Such numbers are absurd, and in light of 22.3% of black South Africans, aged 20 and over, having no schooling, it is easy to see how disparities can continue. The rural areas still do not have the elevatory development, like schools or utilities, that need to really put a dent into the legacy of Apartheid.

The Apartheid legacy goes even farther when it comes to the rise of violent xenophobia, particularly against migrant laborers from a neighboring country like Mozambique. Southern Mozambique has almost always been economically dependent on the exportation of migrant labor to neighboring South Africa. The only main railway line to export goods had to go south-west into a South African port!

The extent of culpability that ZA has in regards to the poor economic situation in neighboring countries is such an extent, it surpasses that of the United States. Mozambique is a perfect example as after it gained independence in 1975, it was thrust into the Mozambican Civil War (1977 – 1992).

The war was fought between the Marxist and Pan-Africanist Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique or FRELIMO) and the anti-communist Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (Mozambican National Resistance or RENAMO). FRELIMO, like many bordering militant Marxist groups, allowed Umkhonto we Sizwe (Xhosa for Spear of the Nation or MK) to operate freely from its territory. MK is the armed wing of the ANC, which took up arms after the police massacred 69 black protestors in the Sharpeville Massacre (March 1969).

RENAMO was originally sponsored by Rhodesia, but from the beginning, the South African military gave direct military aid to RENAMO. Beyond that, ZA provided air support, helicopter insertion, and after the victory of Robert Mugabe in the Rhodesian elections (afterwards Zimbabwe), RENAMO was directly incorporated into the ranks of the South African military hierarchy as ZA troops. Afterward the war escalated to a full-scale military intervention that was publicly denied.

South African Soldiers in the Central African Republic (CAR)

The ZA military/RENAMO strategy for fighting the war did not go beyond inflicting economic damage upon Mozambique, and this included intentionally destroying every piece of economic infrastructure they could find. From 1982 to 1988, ZA/RENAMO inflicted $898 million worth of material losses (six times the value of Mozambique’s yearly exports). It is no surprise that the war ended with the reforms of the NP government in the early 1990s, and it is no surprise that economic opportunities in Mozambique are currently sub-standard.

A 2018 Pew poll found that 62% of South Africans viewed immigrants as a burden on society by taking jobs and social benefits. 60% of South Africans thought immigrants were more responsible for crime than other groups. The number of immigrants and migrants has been increasing to match this rising xenophobia. From 2010 to 2017, the ZA immigrant population jumped by 100%.

From 2000, to March 2008, there were 67 xenophobic killings, and just in May 2008 there were 62 deaths (21 being ZA citizens). The violence in South Africa comes as an unorganized organic expression of militant nationalist sentiment that is attributable to economic hardship.

In 2019, there was another spike in violence as xenophobic riots centered in Johannesburg. The mob targeted foreign-owned enterprises, and a man was killed during some looting in Cape Town. However, Johannesburg happens to be the commercial center of the country, and wealth inequality in Jo-burg is worse than in other major cities like Cape Town.

Make no mistake, South Africa is by far the dominant economic power on the continent, and there is no indication (or real reason) why the influx of migrants should stop. ZA accounts for 24% of the continent’s GDP and produces over 45% of Africa’s electricity. The issue is that this economic success is built on an economic foundation that assumed/concentrated it all into the hands of a handful of white urban centers. ZA is in BRICS with 25% unemployment.

Aside from xenophobia and economics, perhaps the worst problem facing the nation is sexual violence against women. The Department of Police (of ZA) found that c. 3,000 women were murdered between April 2018 and March 2019. The death of 19 year-old Nene Mrwetyana by a postal worker, Luyanda Botha, sparked massive demonstrations across the country. The feminist movement is still ongoing and active. It is for femicide that South Africa frequently gets into the headlines.

Roughly 20 years after the end of Afrikaner rule, in 2010, ZA had a (H)uman (D)evelopment (I)ndex of .347, 25% unemployment, and 50% of the population under the poverty line. Despite this, South Africa is still a major cultural and economic center, and without South Africa, the prospects for southern Africa would not be as bright.

South Africa is proof that racist regimes can be overcome, but it is also evidence that the contradiction and conflict between the old and new regime do not end with a de jure victory. Keeping a close eye on how South Africa works to overcome broad and seemingly unrelated societal issues is valuable in its own right. It is far too common in the United States that the progressive perspective overlooks Africa, its history, and the tangible failures and victories that highlight the present South African political climate.

Sources:

i. Francis B Nyamnjoh. “Excorsing the demons within: Xenophobia, violence & statecraft in contemporary South Africa.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies. 32:3 (2014).

ii. Jason Burke. “‘We are a target:’ Wave of xenophobic attacks sweeps Johannesburg.” The Guardian. 10 September 2019.

iii. Nickolaus Bauer. “South Africa: Protestors demand action on violence against women.” Al-Jazeera. 13 September 2019.

iv. Christine Tamar. Abby Budiman. “Violence in South Africa spreads to Cape Town.” The Guardian. 23 May 2008.

v. “South Africa profile – Timeline.” BBC. Accessed 19 June 2020.

vi. “South Africa gets gender balanced cabinet.” BBC. 30 May 2019.

vii. Pumza Fihlani. “South Africa’s election: Five things we’ve learnt.” BBC. 11 May 2019.

viii. “South Africa elections: Is the gap between rich and poor widening?” BBC. 1 May 2019.

ix. Michael Neocosmos. “From ‘Foreign Natives’ to ‘Native Foreigner’: Explaining Xenophobia in Post-Apartheid South Africa.” CODESRIA. (Dakar:2010).

x. “New era as South Africa joins BRICS.” southafrica.info. 11 April 2010.

xi. Thuso Khumalo. “South Africa Declares ‘Femicide’ a National Crisis.” VOA. 20 September 2019.

xii. “The South African Economy.” showme.co.za. Accessed 5 November 2019.

xiii. OECD

xiv. “Education at a glance 2019: South Africa. OECD. 2019.

xv. The World Bank

xvi. “Overcoming Poverty and inequality in South Africa: An Assessment of Drives, Constraints, & Opportunities.” The World Bank. March 2018.

xvii. William Beinart. “Twentieth-Century South Africa.” Oxford University Press. (Oxford:1994). (2nd Edition:2001).

xviii. William Minter. “Apartheid’s Contras: an inquiry into the roots of the war in Angola and Mozambique.” Zed Books Ltd. (London:1994).