A decade-long dispute between Ethiopia and Egypt (supported by Sudan) over the construction of a 4.6 billion USD hydroelectric dam along the Blue Nile River, within Ethiopian borders, has brought the question of who “rightfully” owns the Nile into the limelight. The infrastructure project called the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), or the Blue Nile Dam, is almost completed. Ethiopia anticipates that the first stage of electrical production will begin as early as 2021, and they claim to have achieved their first-year filling target in mid-July of 2020.1

The construction of the dam and the filling of the water go hand in hand…The filling of the dam doesn’t need to wait until the completion of the dam. – Ethiopian Water Minister Dr. Seleshi Bekele2 3

Ethiopian Minister of Water, Irrigation, and Energy Dr Seleshi Bekele

The importance of the Nile river to the 11 countries (Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania) that occupy the almost 7,000 km long Nile River Basin cannot be understated. It is not a coincidence that the site of the world’s longest river is also the site of the world’s oldest and most foundational civilizations.4

The coverage of the on-off talks, hosted by the African Union between the two downstream riparian republics and Ethiopia, has frequently painted Ethiopia as callously disregarding the real, valid threat to the Egyptian potable water supply. Egypt claims that without an international legally-binding mechanism to govern the filling of/flow of water through the dam, specifically during “dry years,” that Ethiopia will effectively cut-off the freshwater supply for the people downstream. Following Egypt’s logic, it is due to this obvious need for international cooperation that the filling of the dam must be postponed.5 6 7

The Nile is fed by two tributary rivers—the White Nile and the Blue Nile—that converge within Sudan, at the capital of Khartoum, to form the Nile river proper. The head of the White Nile is in Lake Victoria in Uganda, and the head of the Blue Nile is Lake Tana in Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Blue Nile contributes a whopping 80% of the waters going into the Nile proper, and for Egypt’s c. 100 million people, the Nile is where they draw 90% of their freshwater. Considering that the Blue Nile Dam is being built only c. 15 km from the Sudanese border, this single construction holds sway over the freshwater supply of an estimated 72 million Egyptians.8

Certainly, this is what Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry has been pushing. In an interview with the Associated Press, Shoukry claims, “The responsibility of the security council is to address a pertinent threat to international peace and security, and certainly the unilateral actions by Ethiopia in this regard [filling the dam] would constitute such a threat.” 9

Foreign Minister Shoukry on a visit to Occupied Palestine to see ‘Israel’

The concession by Ethiopia to postpone the unilateral filling of the GERD has been the primary condition that the talks are dependent upon.10

The entire Egyptian case is built upon the premise of a potentially prolonged drought affecting the Nile. The validity of the Egyptian position begins to fall apart when one considers how historically unprecedented an Egyptian drought would be. It is the preservation of the ancient Egyptian written record that undermines Shoukry’s standpoint.11

On Sehel Island in the Nile, ironically near Egypt’s Aswan High Dam, there is a stele, known as the Famine Stela, that bares an inscription about a seven-year drought (and subsequent famine), c. 26th century BCE, that occurred during the reign of Pharaoh Djoser (of the Third Dynasty). Egypt has not had a drought since.12

Considering the fact that for the last c. 4,200 years Egypt has not had a single instance of drought, and considering that 80% of the Nile comes from Lake Tana, then the entire premise of a potential upstream Ethiopian drought is moot.

What Egypt really fears is the loss of its monopoly over the Nile River Basin. The importance of the Nile river to the 11 countries (Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania), not just Egypt, that occupy the almost 7,000 km long Nile River Basin cannot be understated. It is not a coincidence that the site of the world’s longest river is also the site of the world’s oldest and most foundational civilizations.

For such an obviously vital transnational resource, Egypt and Sudan have claimed it is their ‘natural right’ to dictate how the upstream nations use the river’s water. Both nations frequently point to the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement in which Egypt is allocated 55.5 B m3 a year and Sudan 18.5 B m3 a year. Keep in mind that roughly 960 B m3 are discharged by the Nile annually. The 1959 treaty was solely between Cairo and Khartoum, under the British crown, and Ethiopia was not involved in any way.13 14 15 16 17

[The 1959 Nile Waters Agreement can be found HERE]

The (G)rand (E)thiopian (R)enaissance (D)am Site

In the 1959 treaty, which was an update to a 1929 Anglo-Egyptian treaty, the UK recognizes Egypt’s ‘natural right’ to command the whole river. This right, which the UK had no right to write away to Egypt, originates from intercolonial treaties to demarcate their new-found ‘territories’. Starting with the 1891 Anglo-Italian Protocol to an agreement with King Leopold II of Belgium to the 1959 treaty, Ethiopia has not signed one, and Shoukry wants the world to believe that Europe has the authority to violate African sovereignty.18

[The treaties are covered at length HERE]

Egypt is prepared to enforce its aquatic hegemony through force if necessary. In 1978, Ethiopia wanted to build a series of dams (Egypt has two) along the Blue Nile, but Egyptian president, Anwar El-Sadat, suggested he would sooner go to war with Ethiopia than tolerate the building of these dams. Egypt has again followed this historical pattern as they have threatened a “potential armed conflict” if the UN does not intervene soon.19 20

If Ethiopia builds one, then the other nations of the Nile River Basin will revive previously discontinued aquatic infrastructure projects.21

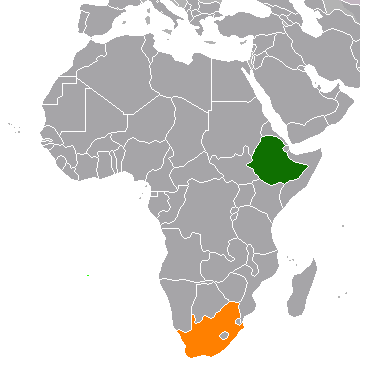

On that same note, the importance of the GERD project to Ethiopia cannot be understated. Ethiopia’s population is growing twice as fast, and despite having roughly the same population, only 44% of Ethiopia have access to electricity (vs Egypt’s 100%). Ethiopia hopes the dam, when full, will generate 6,000 megawatts of power. Currently, 45% of all electricity is produced in South Africa, and Ethiopia is striving to become the dominant African energy-exporter.22 23

South Africa (Orange) and Ethiopia (Green)

[Want to read about South Africa? Click HERE]

The GERD will lift millions out of poverty, and not just in Ethiopia, but in Tanzania and Rwanda as well. This project will benefit all African nations in the region, and the power will not be hoarded. Egypt has two dams, the Aswan High and Low Dam, and their construction has not benefited their neighbors in any positive way to date.

Currently, 55% of Ethiopia relies on firewood to cook their food, and this is NOT their intention. At the start of the 21st century, Egypt used 80% of the Nile and Ethiopia only used 1%. It is time that Ethiopia used its God (SWT) given right to use the Blue Nile, and Egypt must accept that in the new post-colonial order, sovereignty needs to be respected–not trampled.24 25

- Ulf Laessing. Nayera Abdallah. Khaled Abdelaziz. Kevin Liffey. “Egypt and Sudan criticise Ethiopia at start of new Nile dam talks.” Reuters. 28 July 2020.

- Dawit Endeshaw. John Stonestreet. “Ethiopia has started filling Grand Renaissance dam on Blue Nile – water minister.” Reuters. 15 July 2020.

- “Ethiopia begins filling Grand Renaissance dam on Blue Nile.” Al-Jazeera. 16 July 2020.

- Nebiyu Tedia. “In-depth analysis: past agreements on the Nile in view of the law of treaty and the CFA.” Addis Standard. 11 October 2017.

- Ulf Laessing. Nayera Abdallah. Khaled Abdelaziz. Kevin Liffey. “Egypt and Sudan criticise Ethiopia at start of new Nile dam talks.” Reuters. 28 July 2020.

- “Sudan Expresses Reservation Over the Ethiopian Unilateral Move of Filling the Dam.” Sudan News Agency. 27 July 2020. Accessed on allafrica.

- Lee Keath. Samy Magdy. “AP Interview: Egypt wants UN to avert unilateral fill of dam.” Associated Press. 22 June 2020. Accessed on abcnews.

- Ulf Laessing. Nayera Abdallah. Khaled Abdelaziz. Kevin Liffey. “Egypt and Sudan criticise Ethiopia at start of new Nile dam talks.” Reuters. 28 July 2020.

- Lee Keath. Samy Magdy. “AP Interview: Egypt wants UN to avert unilateral fill of dam.” Associated Press. 22 June 2020. Accessed on abcnews.

- ibid.

- Muluken Bekele. “Ethiopia’s struggle for equal share of the Nile.” Oromo Patriot. 23 May 2020.

- ibid.

- ibid.

- Nebiyu Tedia. “In-depth analysis: past agreements on the Nile in view of the law of treaty and the CFA.” Addis Standard. 11 October 2017.

- “Ethiopia begins filling Grand Renaissance dam on Blue Nile.” Al-Jazeera. 16 July 2020.

- Aidan Lewis. Andrew Heavens. “Factbox: Key facts about Ethiopia’s giant Nile dam.” Reuters. 6 November 2019.

- “Agreement between the Republic of the Sudan and the United Arab Republic for the full utilization of the Nile waters signed at Cairo, 8 November 1959.” United Nations. Treaty Series. (Vol. 453|No. 6519).

- Nebiyu Tedia. “In-depth analysis: past agreements on the Nile in view of the law of treaty and the CFA.” Addis Standard. 11 October 2017.

- Timothy Kaldas. “Why Egypt And Ethiopia Can’t Reach a Dam Deal.” Bloomberg. 23 July 2020.

- Muluken Bekele. “Ethiopia’s struggle for equal share of the Nile.” Oromo Patriot. 23 May 2020.

- ibid.

- ibid.

- “The South African Economy.” showme.co.za. Accessed 5 November 2019.

- Muluken Bekele. “Ethiopia’s struggle for equal share of the Nile.” Oromo Patriot. 23 May 2020.

- Nebiyu Tedia. “In-depth analysis: past agreements on the Nile in view of the law of treaty and the CFA.” Addis Standard. 11 October 2017.